Written on 3:09 PM by waratxe

langstabil - Pronto Luigi (Blanco/May) published by: MHz/Plate Lunch (4/2000)

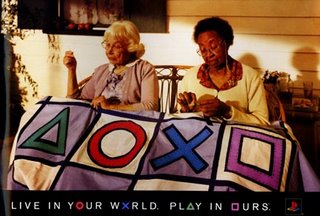

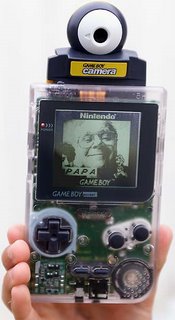

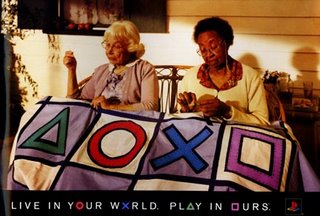

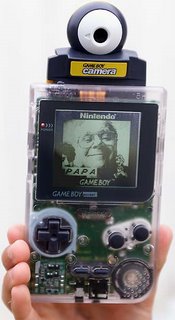

"Gioco Bambino", the recent CD-release of the german duo "Klangstabil", includes 12 tracks of Gameboy electronics that

range from simple melodies that could easily be used as themes for childrens TV-series, to speedy, crackling, rumbling and noisy tracks. All of these tracks have been recorded directly onto DAT in realtime by using only a Nintendo Gameboy with an additional Gameboy Camera cartridge (which wasn't used to take pictures with, but as a primitive "mixing desk") and some simple effects. There are no samples, overdubs or additional instruments mixed to this recording later - all that you hear are the gameboy sounds recorded directly onto a DAT-recorder! About 70% of the tracks included are made by using only the gameboy and nothing else. The remaining 30% of the tracks are recorded while the gameboy has been connected with additional electronic equipment, but of course these tracks are recorded in realtime, too. "Gioco Bambino" - what means "game boy" in italian language - evolved out of the spontaneous idea to release a complete CD with pieces played on a Gameboy only. Receiving a track by "Klangstabil" that had been recorded this way, "plate lunch" was immediately fascinated by this idea and asked "Klangstabil" to do further experiments and recordings with the gameboy for a CD-release in co- operation with their label, which finally resulted in about 20 tracks that they recorded during April and November 1999 and of which the 12 most interesting ones found their way onto the "Gioco Bambino" CD. It's really exciting to listen to music that comes straight from the heart of a tiny gameboy. The german duo of "Klangstabil" was founded in late 1994 by Maurizio Blanco and Boris May. Amongst their releases are the brilliant "Böhm - Gott der Elektrik" LP from early 1997, that was released on their own "Megahertz" label. On this LP they used a self-converted "Böhmat", a rhythm-and effects-"instrument" which had its high time during the 50's and the 60's and that was originally intended to support organ-players with additional rhythms. "Klangstabil" showed that the "Böhmat" is much more than just a simple instrument for support, but that it deserves to play a main part next to other instruments with its astonishingly fresh sound, instead of being kind of a musical slave. Due to their 1998 LP-release "Sieg der Monochronisten" and an appearance on the 2-CD-compilation "Tekknoir" that has been released on the german "Hymen" label, a sub-label of "Ant Zen" - which recently released further tracks made with the gameboy as 12"-LP with the title "Sprite Storage Format" (the 500 copies sold out within two days from the label!) - "Klangstabil" have been labelled as "post-industrial"-outfit, but releases like the "Böhm" LP and their so far sole 7" - which both got enthusiastic reviews in the german "De:Bug" magazine for example - as well as the recent "Gioco Bambino"- CD show, that such labels don't do them justice. "Klangstabil" establish their own rules what results in releases that are fairly different to each other. Asked, how they would describe their music, they say that it's just "Klangstabil music" - what only shows their aversion against all kinds of labels. They do their very own thing - probably sitting between all chairs, as on one hand they're working with acoustic "Orff"-instruments - an project they realize with the help of children and to the other hand they record minimal, but harsh electronic pieces which definitely show influences by old school electronic/industrial artists like Conrad Schnitzler or Maurizio Bianchi/M.B., perfectly connected with their present sound experiments. Recently they performed some of their gameboy tracks on the "Mixer" Festival in Amsterdam, along with artists like V/VM, Saoulaterre, Gert-Jan Prins, Kapotte Muziek and others. Maurizio Blanco and Boris May will always have an open ear for interesting sounds - there's absolutely no doubt about it!

|

Written on 3:05 PM by waratxe

Is the Pen as Mighty as theJoystick?

By MATT RICHTEL

Published: March 5, 2006

WHEN the package showed up last November at his house outside of Portland, Ore., David Hodgson initially felt a wave of great excitement. But that promptly gave way to foreboding.

Alan Weiner for The New York Times

David Hodgson has written 55 strategy books for video games. "It's like writing a travel guide to a place that doesn't exist," he said of his work.

Forum: Gaming

Enlarge This Image

Larry W. Smith for The New York Times

Beverly McClain bought about a dozen strategy guides last year, more than the number of novels she bought.

As soon as he opened the bundle, he realized that a clock had started ticking on a new assignment: he had four months to write a manual on how to extort, kill and otherwise take over a New York mob family. The task was particularly harrowing, in part because he wanted to make sure that his prose was well organized and clear.

Inside the package was an early copy of the much-anticipated Godfather video game that its maker, Electronic Arts, is scheduled to release later this month. Mr. Hodgson's job was to understand every facet of the game and to write a book advising players about how to win it.

For players of Godfather, which is based on Mario Puzo's novel and Francis Ford Coppola's movies, the goal is to rise from small-time hustler to boss of the Corleone crime family or, ultimately, all of the area's crime families. Doing so requires players to complete 17 missions, to attempt 20 assassinations and to bribe and extort dozens of merchants.

The game, like a growing number of others these days, takes place in a world where the players can move freely; it does not have the prescribed limits of, say, Pac-Man. And that creates special challenges for the author of a strategy guide.

"The first thing I thought was, 'I need a map,' " said Mr. Hodgson, 33, who spent the first part of his time getting to know New York and New Jersey, where the game is set. With help from the company, he also familiarized himself with a range of weapons, the best ways to blow up buildings and how to extort various characters. There are 50 to 60 ways to murder people in the game — from running them over with cars to garroting — and many ways to shake down a merchant.

After logging long hours trying various tactics, Mr. Hodgson said he asked the company whether he had explored them all, and which ones would help players rack up the highest scores.

Mr. Hodgson's name may not ring a bell, perhaps not even with most of his readers. But he is a best-selling author, one of a platoon of 25 or so professional authors turning out books — strategy guides for video games — that can sell hundreds of thousands of copies.

The guide for Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, an intricate and violent action game, has sold 748,000 copies, an unusually high number, since it came out in 2004. Mr. Hodgson estimates that the 55 strategy guides he has written have sold a total of one million copies.

(By comparison, former President Bill Clinton's autobiography, "My Life," which came out in 2004, has sold 1.27 million copies, according to Nielsen BookScan; the hardcover edition of "My Life" was on the New York Times best-seller list for 28 weeks.)

Video games are not usually associated with reading, so the strategy guides' popularity is something of an oddity, marrying the fast-paced, fast-twitch world of computer and television console games with the tactile and ruminative experience of text-centric manuals.

In general, strategy guides are thick full-color books that tell players how best to solve puzzles, find and use weapons, discover hidden bounty and navigate complex and expansive virtual worlds — worlds that the writers are paid to deconstruct.

"It's like writing a travel guide to a place that doesn't exist," Mr. Hodgson said. "Whereas Frommer's guides tell you what hotel to stay in, I tell you which hotel not to stay in because you're going to get dragged down by a gangster."

BY most measures, strategy guides are not a huge business. They generated about $90 million in sales in 2004, according to the NPD Group, a market research firm; the figure dropped to $67 million in 2005, but that decline was expected as a cyclical moment, paralleling a transition in the industry to a new generation of advanced game consoles. If history is any guide, industry executives expect the transition to lead eventually to increased sales of games and strategy manuals.

The challenge for the industry's two biggest publishers — Prima Games, a division of Random House, and BradyGames, a subsidiary of Pearson — is how to capitalize on computer technology without being undone by it. In a world of virtual play, they want to prove that a physical book is the best, most effective sidekick.

To do so, these companies are fending off challenges from Internet publishers, both shoestring amateurs and well-financed professionals, that produce online guides. Ziff Davis, the publisher of PC Magazine and other consumer technology publications, plans to start a free game-focused Web site in March; among other things, it will offer video of people playing games, to show players how to solve challenges.

Among the books that are published by BradyGames are guides for navigating through the video games Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas and World of WarCraft.

Forum: Gaming

"There's a lot of free content on the Web, and we've been battling it for years," Steve Escalante, director of marketing for BradyGames, said in an interview.

In competing with these free rivals, BradyGames, based in Indianapolis, and Prima, in Roseville, Calif., have the advantage of extensive cooperation from game makers, which provide full schematic diagrams, for example, for the games and images. In exchange, they pay a lump sum and a percentage of sales.

It seems to be working. Mr. Escalante said that despite the free online competition, "we continue to grow."

For those who use the guides, the efforts of Mr. Hodgson and other authors are worth more than the $15 to $20 they typically spend on the books. Indeed, while Mr. Hodgson has never met a woman named Chloe Brown, an avid video game player in Toronto, he has helped her keep her frustration in check.

"I once threw my controller into the wall and broke it" while playing an adventure game called Jade Empire, said Ms. Brown, 21. She was stuck at a certain point, she explained, and became frustrated because she couldn't figure out how to advance; after breaking her controller, she bought the game guide by Mr. Hodgson.

Generally, Ms. Brown and others who buy guides said they need help to cope with the growing complexity of games. In the days of simpler games, "you opened the door, smacked someone on the back of the head and walked out of the room," Ms. Brown said. "Now you have to peek into the doorway, creep into the room, create a disturbance, subdue someone: Are you going to kill them? Will you use a silencer? Or will you just knock them out?"

If you make the wrong move, she added, "you can go through the same process 5, 10 or 25 times before you realize 'this is what I'm supposed to do.' "

The guides give explicit counsel. One page in the manual for Call of Duty 2: Big Red One, an adventure and shooting game set in World War II, even advises players to beware of French soldiers collaborating with the Nazis. "Follow Bloomfield up the stairs to the entrance of the hangar," it reads. "Shoot out the windows and use the windows as cover to fire down at the French. Watch out for the guys on the catwalk directly across from you; they can see and fire at you."

It adds, helpfully: "Be careful not to accidentally shoot your teammates."

Some players disdain the guides, which they say are less about strategy than taking shortcuts.

"They're good for people who don't like challenges," said Ibe Ozobia Jr., 32, of Las Vegas. "You don't have to think through the game. You can just look for the answers on the shelf."

Others, however, swear by them. Beverly McClain, 60, a retired clerical worker in Wichita, Kan., said: "Many gamers insist that the only way to play a game is to figure it all out for yourself. I say, buffalo chips."

Ms. McClain says she plays video games about five hours a night. As her taste in entertainment shifted from reading books to playing the games, she said, her purchases at bookstores also changed. She said she brought home about a dozen strategy guides last year, more than the number of novels she bought.

Ms. McClain tried to use free information provided online, she said, but it required her to print out dozens of pages of instructions, or to switch her computer screen back and forth between the game and the hints.

AS games have become more complex, guidebooks have grown longer. Debra Kempker, the president of Prima Games, said the average size of a guide for a console-based game is 176 pages, up from 128 pages in 2002.

The growing complexity means that Mr. Hodgson and other authors often cannot deconstruct the games without assistance. Mr. Hodgson says he typically receives ample help from the game designers for the eight guidebooks he is under contract to write each year for Prima Games — but not always. In 2003 and 2004, he said, designers at Atari were too busy to give him much help in writing a guidebook for its "Driv3r" game.

Despite such occasional problems, he says he considers his job a dream. While growing up in Manchester, England, where his father taught geography at a university and his mother taught German and French, he planned to become a history teacher. But he became interested in games — he found that his interest in detail and research was served by unlocking their virtual worlds.

In 1997, Mr. Hodgson wrote his first guide, for Turok: Dinosaur Hunter. Last year, he wrote guides for, among others, Star Wars Knights of the Old Republic II, Medal of Honor: European Assault, Half Life 2, Jade Empire, Burnout: Revenge, and Perfect Dark Zero.

He declined to say how much he is paid for each guide, but publishers say they generally pay authors $3,000 to $12,000 a book. For the Godfather guide, he wrote 175,000 words — the equivalent of nearly two novels — and said he talked daily to a designer who was laying out images from the game, tip boxes and other elements.

By the time he finishes a project, Mr. Hodgson said, he is sometimes so sick of the game that he hopes to never see it again, much less play it.

But he said he mostly loves the work, and even likes the relative anonymity of his authorship. Sometimes, it can be amusing. At the annual E3 trade show — the year's biggest gathering of video game companies — Mr. Hodgson's publisher placed him at a booth to sign copies of the strategy guides he had written.

"The most amusing thing is, some people will ask for a copy of the book and ask me not to sign it," Mr. Hodgson said, laughing. He doesn't fault them. "I'm not a proper author," he said. "I'm the redheaded stepchild of authors."

|

Written on 3:02 PM by waratxe

Acuden más de 30 mil personas a olimpiadas de videojuegos

Los aficionados a los juegos electrónicos disfrutaron en pantallas gigantes los juegos cruciales de la competencia, mientras que la gran final fue transmitida por internet

Andrés Eloy Martínez Rojas

El Universal

Martes 22 de noviembre de 2005

14:51 Por muchos considerada las olimpiadas de los videojuegos, el World Cyber Games 2005, culminó este fin de semana en Singapur con la participación de 39 mil espectadores.

La competencia contó con 700 participantes provenientes de 67 países, quienes se disputaron 435 mil dólares durante dos días de concentrados combates de láser en 600 computadoras y 30 consolas Xbox, en las que se llevaron a cabo mil partidas, de acuerdo a la revista New Scientist.

Los aficionados a los juegos electrónicos disfrutaron en pantallas gigantes los juegos cruciales de la competencia, mientras que la gran final fue transmitida por internet.

Entre los participantes se encontraban jugadores de video juegos profesionales como Niklas Timmermann, de Alemania, quien jugo el juego de simulación de carreras de autos Need for Speed y Jihoon Seo, de Corea del Sur, quien mostró su destreza en el juego de estrategia StarCraft.

Durante el evento , 12 mil kilowatts de electricidad fueron utilizados en el International Conventional and Exhibition Center, sede de la competencia.

Olimpiada electrónica

Hank Jeong director de mercadotecnia del evento, aseguro que “con la sin precedente participación de espectadores y concursantes de todo el mundo este año, World Cyber Games ha verdaderamente evolucionado y se ha convertido en el equivalente de las Olimpiadas".

El score final favoreció a Estados Unidos, que se llevó la medalla de oro por juegos como CounterStrike y Halo 2, así como una medalla individual de plata por el juego de estrategia WarCraft III.

Estados Unidos fue seguido muy de cerca por Corea del Sur, que ganó dos medallas de oro y una de bronce, y de Brasil, que coleccionó una de oro y dos de plata.

Medallas individuales de oro se otorgaron a Alemania por el juego FIFA Soccer y a China por WarCraft III.

Los participantes en este torneo necesitaron tomar parte en competencias nacionales para ser elegidos para el máximo evento.

Éstos fueron los nueve videojuegos en los que se batieron los competidores fueron Counter Strike, FIFA Soccer 2005, Need for Speed, StarCraft, WarCraft III, Warhammer, Dead or Alive Ultimate, Halo 2 y Freestyle.

dm

|

Written on 3:04 PM by waratxe

territorio sonoro

ricardo farias

partitura en unos y ceros

En una cultura donde cada vez más la concatenación de imágenes –visuales- dificultan la total o parcial apreciación del sonido, en una ciudad donde las provocaciones gráficas se prestan a los juegos más bajos de seducción para convertirse en la primera referencia del día. En este territorio de la imagen marcaremos por esta vez el mapa sonoro de la música para videojuegos.

Bajo un contexto completamente lúdico, altamente tecnológico, multidimensional y mediático, los videojuegos y en específico la música para los mismos son hoy un referente en el mundo; para colocar algunos números: sólo del mítico videojuego Final Fantasy hay un aproximado de ciento cincuenta álbumes editados y solamente 3 son compilaciones: versiones en orquesta, pop, tributos, un verdadero caso de culto; Super Mario Bros. otro legendario videojuego tiene alrededor de noventa discos, tratamientos de los mismos temas en jazz, piano, electrónica y otros géneros.

Pero no siempre fue así, en los primeros años de la década de los setenta las consolas para videojuegos tenían escasa memoria y la única forma de incluir sonidos era a través del MIDI -musical instrument digital interface-, instrumento que les permitía a los creadores generar sonidos entretenidos y graciosos que ayudaban a mejorar el entorno gráfico del videojuego, que para esos tiempos era muy limitado* . Más adelante los mismos creadores utilizaron el MIDI ya como una herramienta de creación musical y generaban “temas” para los videojuegos, seguían siendo limitados, pero apaleaban ya a ciertas armonías o melodías muy sencillas que nos llevaban en una línea narrativa que nos decía incluso cuándo llegábamos a una parte importante del juego.

Procurando ubicar la importancia de la música para este tan controvertido medio, aparecen ejemplos que nos permiten apreciar su trascendencia. Si bien los juegos GTA III, Vicecity y San Andreas han sido altamente criticados por sus contenidos violentos y discriminatorios*** , le dieron a los videojuegos un matiz interesante, como parte del juego el personaje principal utiliza automóviles que pueden sintonizar estaciones de radio musical que el conductor puede ir cambiando vía un comando en el control; en el caso específico de los últimos dos, Rockstar (el estudio que los produce), compró los derechos de canciones de figuras como Michael Jackson, Black Eye Peas y muchos más, esto ha tenido tanto éxito que se han editado ocho discos de la versión Vicecity y once para San Andreas**.

Sin duda la música le brinda a los videojuegos un soporte cada vez más complejo y polifuncional, desata por ejemplo grandes conciertos orquestales en Japón y Estados Unidos, provoca la creación de bandas de rock como Mini Bosses que tocan música de videojuegos como Megaman y Castlevania, inspira la creación de estaciones de radio (GAMING FM: http://www.gamingfm.com/complete/main/), participación de agrupaciones reconocidas como The Cardigans o Incubus en los soundtracks y conectando todos lo puntos, le da a la cultura de los videojuegos un nivel más de diversión, reflexión y debate, que por lo visto tiene mucho camino por recorrer.

*Por poner un ejemplo de consola para videojuego: ATARI 2600, donde los sonidos eran mínimos y amenizaban la sesión o el nivel que estaba jugando el usuario.

**Para más referencias: http://www.rockstargames.com

***Con la violencia hacia las mujeres no se juega. Videojuegos, discriminación y violencia contra las mujeres: http://www.es.amnesty.org/index.php

Para más referencias: http://minibosses.com/

|

Written on 12:56 PM by waratxe

November 22, 2005

Making Artists

Video Games Are Their Major, So Don't Call Them Slackers

By SETH SCHIESEL

"So you have these four basic types that occupy the environment: the Achiever, the Explorer, the Socializer and the Killer."

Nick Fortugno, the 30-year-old teacher, turned away from the whiteboard and faced the 14 undergraduate and master's-level students in his Thursday seminar. "Killers act like predators, and like any ecosystem, if you increase the number of killers and facilitate them, you decrease the number of achievers and socializers."

A forestry class on the ecology of the African savannah? No. A psychology course on the ways of the grade-school playground? Closer, but not quite.

Rather, in his video game design seminar at Parsons the New School for Design in Greenwich Village, Mr. Fortugno was recently explaining the basic taxonomy of players in online role-playing games like World of Warcraft or Lineage, games that millions of people around the world play every day.

"You might think that killers are just bad for the game, right?" he said. "Well, they actually provide a really valuable social function: they provide something for other players to talk about. 'Oh, my God, did you hear that Dorag407 got killed last night at the dungeon?' See, all of

these things exist in a social network, which is what really provides the game experience."

Most of the students kept pecking at their laptops. A few took notes the old-fashioned way.

Three decades after bursting into pool halls and living rooms, video games are taking a place in academia. A handful of relatively obscure vocational schools have long taught basic game programming. But in the last few years a small but growing cadre of well-known universities, from the University of Southern California to the University of Central Florida, have started formal programs in game design and the academic study of video games as a slice of contemporary culture.

Traditionalists in both education and the video game industry pooh-pooh the trend, calling it a bald bid by colleges to cash in on a fad. But others believe that video games - which already rival movie tickets in sales - are poised to become one of the dominant media of the new

century.

Certainly, the burgeoning game industry is famished for new talent. And now, universities are stocked with both students and young faculty members who grew up with joystick in hand. And some educators say that studying games will soon seem no less fanciful than going to film school or examining the cultural impact of television.

According to the International Game Developers Association, fewer than a dozen North American universities offered game-related programs five years ago. Now, that figure is more than 100, with dozens more overseas. At Carnegie Mellon University, a drama professor and a computer science professor have created an entertainment technology program that now enrolls 90 students and will soon open branches in Australia and South Korea.

At the Georgia Institute of Technology, which started new undergraduate and Ph.D. programs in interactive media last year, the director of graduate studies at the university's liberal arts school likens the multiple outcomes possible in video games to the magical realism of writers

like Borges.

"The skills and methods of video games are becoming a part of our life and culture in so many ways that it is impossible to ignore," said Bob Kerrey, the former Nebraska senator who is now president of the New School, which includes Parsons. Parsons has offered game courses to graduate students for five years and this fall began an undergraduate program in game design.

"But if you just look at the surface of people playing games, you are missing the point, which is that games are all about managing and manipulating information," Mr. Kerrey said. "A lot of students that come out of this program may not go to work for Electronic Arts. They may go to Wall Street. Because to me, there is no significant difference - except for clothing preference - between people who are making games and people who are manipulating huge database systems to try to figure out where the markets are headed. It's largely the same skill set, the critical thinking. Games are becoming a major part of our lives, and there is actually good news in that."

It is certainly good news to students like Johnny Trinh, 18, a Parsons sophomore from Queens.

"When I came here, I was really surprised that they had so much in-depth set aside for people who want to go into gaming culture," Mr. Trinh said last month during a break in his multimedia programming class as, multitasking, he skimmed the Web message boards for his online gaming team. "When you talk to your parents, they want you to be a doctor or a lawyer, but they are starting to understand that you can have a real job making games, and among the students it is definitely becoming more popular."

Electronic Arts, the No. 1 game maker, based in Redwood City, Calif., has been a leader in encouraging universities to develop game programs. Last year, the company, which is known for franchises including Madden football, contributed millions of dollars to help underwrite a new three-year master of fine arts program in interactive entertainment at U.S.C.

"For 20 years, students came out of school and they had to kind of unlearn what they had learned in computer science, and the stuff they haddone in art wasn't appropriate, and we had to do a lot of training internally," said Bing Gordon, the company's chief creative officer. "The

big idea now is that in the last three or four years, the students are starting to come out of school immediately able to contribute to real projects, which is what we need.

"Just imagine that a movie studio showed up at a cinema school and said, 'You know, we need three times as many directors and screenwriters as we are able to get now.' That's where we are. In all of traditional media there is a glut of people who want jobs, and that makes for some

dog-eat-dog competition. But in our business there still is not as much talent as there is opportunity."

Jason Della Rocca, executive director of the game developers' association, said that no firm figures were available for overall employment in the industry.

But at bellwether Electronic Arts, employment has almost doubled since 2000, to roughly 6,450. Over the same period, the number of employees in Electronic Arts's creative operations - the people who actually make games - has almost tripled, to 4,300.

At universities that have embraced video games, the curriculum varies. Georgia Tech has taken a more humanities-centered approach that focuses on the study of games as cultural artifacts, much as a scholar who has no interest in making television programs might study "All in the

Family" and "The Jeffersons" to try to parse American race relations in the 1970's.

Institutions like Parsons and U.S.C. try to give students both the technical and academic backgrounds to become working game designers. That involves some traditional lectures, but often means assembling students into teams to make games, starting with pen and paper and gradually incorporating more sophisticated technologies.

"To create a video game project you need the art department and the computer science department and the design department and the literature or film department all contributing team members," Mr. Gordon said. "And then there needs to be a leadership or faculty that can evaluate the work from the individual contributors but also evaluate the whole

project."

Most of the game programs are so new that track records hardly exist, but Mr. Gordon said that the master's-level program in entertainment technology at Carnegie Mellon had been the most successful in embracing a multidisciplinary approach and producing work-ready students. That

program, which helped pioneer the field when it began in 1999, is led by the odd couple of Donald Marinelli, a drama professor, and Randy Pausch, a computer scientist.

"When students want to come in and complain that they can't work with people from other disciplines, we tell them to come in and tell us both about it," Mr. Pausch said.

Mr. Marinelli added, "When we first got the program started, we worried about if these hardcore geeks would be able to communicate with the artists. But now we find it common to see applications from people who have an undergraduate major in computer science and a minor in visual arts, or a major in music and a minor in computer science. The students have actually been doing this right brain-left brain crossover on their own."

Yet even some in the game industry express doubts about the merit of such programs.

Jack Emmert had already earned his master's degree in ancient Mediterranean history from the University of Chicago and was working on his Ph.D. in Greek and Latin at Ohio State University when he dropped out in 2000 to become creative director at Cryptic Studios, a game company based in Los Gatos, Calif., where he has helped design the successful City of Heroes and City of Villains online games.

"This whole idea of teaching game design is a fabrication," Mr. Emmert said. "I'm a serious academic, and what is the actual skill that they're teaching? If you're not teaching a quantifiable skill, then you are teaching an opinion. Making games is an art form. You need to understand

the technical side, but I loathe any attempt to teach game design as an academic discipline."

It is a familiar refrain to Tracy Fullerton, a professor involved with many of the new video game programs at U.S.C. She said it reminded her of complaints from Hollywood old-timers in the late 1960's and early 70's when film schools first started producing directors and screenwriters who had spent more time in classrooms than fetching coffee on Hollywood lots.

"There are definitely some people in the game industry who wonder why academia is taking an interest in them after all this time," Ms. Fullerton said. "It reminds me that there was a moment when film studies really took off and the guys at the studios were like, 'Who are these Spielbergs and Lucases and Coppolas coming out of these film schools with these crazy ideas?' They'll come around."

fuente: New York Times on line. imagen: Evan Harper (Parsons the New School for Design)

|

Written on 12:11 PM by waratxe

ricardo farias / Texto: atomix / 507 palabras

las chicas también juegan

ricardo farias (comodecir@yahoo.com.mx)

¿Los videojuegos sólo están en tierra de hombres o las videojugadoras son la última frontera de este territorio? Si hay enigmas dentro del mundo de los videojuegos, uno de ellos sin duda es el de las chicas gamers. ¿Nos parece cool que una chava nos rete en Soul Calibur 3? Mejor aun: ¿Que haya acabado tres veces Kingdom Hearts? ¿Una prenda por cada vez que gane en el FIFA 06? O en realidad nunca nos hemos preguntado cómo compartimos la pasión de jugar con las chicas.

El mundo se está moviendo y por todos lados surge la pregunta sobre el papel de la mujer en los videojuegos. Pensando en chicas y videojuegos, talvez lo primero que nos venga a la mente sea la nueva imagen de Need for Speed o el juego Dead or Alive en donde es más importante el tamaño de los bikinis que llevan puesto las jugadoras, que el partido de volley. Pero el mercado y la cultura se han ido modificando con el tiempo y hoy tenemos visiones compartidas y diversas sobre dónde estamos parados. Por ejemplo:

ORGANIZACIONES

Amnistía Internacional publicó a finales del año pasado un estudio en donde condena a la mayoría de los videojuegos por ser discriminatorios y por atentar contra los derechos humanos. ¿Será esta una intención de los productores de videojuegos? Seguramente no, pero sí nos pone pensar sobre las repercusiones que puede tener un “simple“ videojuego, nos pone a pensar en la responsabilidad que adquiere cada día más jugar y que cada vez podemos ver menos a los videojuegos como un simple juego de niños. Se está metiendo cada vez más en nuestras vidas, en nuestra casa, en nuestra forma de pensar y ver el mundo.

MERCADO

Por otro lado las mujeres han ganado terreno y atención de los productores y distribuidores de videojuegos, y no necesariamente porque estos estén tan preocupados por que sus títulos discriminan a la mujer, la razón: se han dado cuenta que son un terreno no explotado y que hay gran potencial en el mercado femenino. Se han hecho intentos por conectar a las chicas gamers, con juegos rosas, bonitos y cursis, la mayoría fueron un fracaso. Los productores se dieron cuenta que no era por ahí y que su público era mucho más complejo de los que pensaban. En otras palabras aparecen nuevos mercados en los videojuegos, aumenta el promedio de edad del gamer, se modifica la segmentación de los públicos y hoy más que nunca tenemos un gran abanico de propuestas y de audiencias.

Es momento de pensar que ya no hay juegos para niños y para niñas, que posiblemente las compañías desarrolladoras estén pensando más en perfiles de jugadores que en el sexo de los gamers. en un mercado cada vez más competido, los directores de juegos no consagrados tendrán que pensar que las niñas también juegan y al mismo tiempo romper sus paradigmas sobre qué quiere decir eso, pensar que Lara Croft no lo es todo y que las chicas gamers ya cruzaron la frontera.

|

![]()